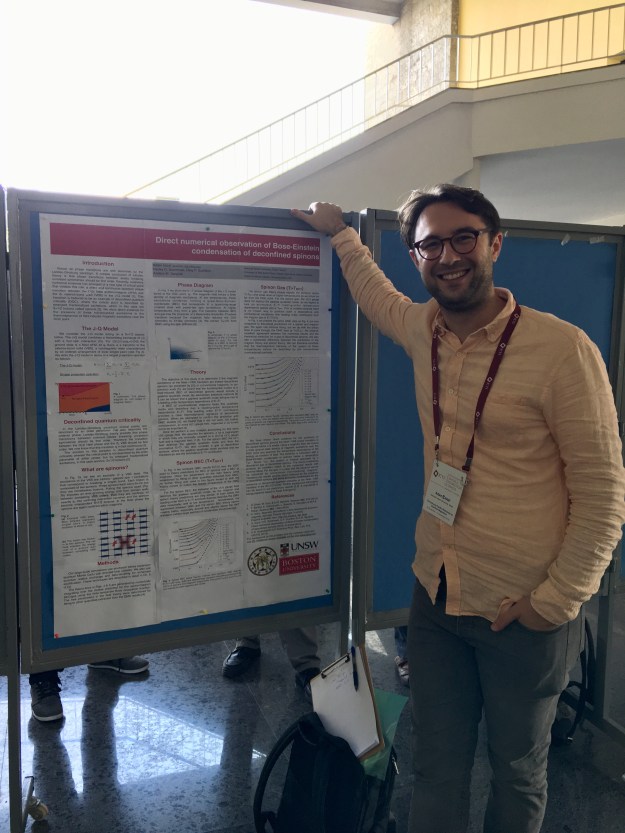

Science is a powerful way of learning how our world works, but that knowledge is useless if ordinary people don’t trust scientists. This lack of trust is at the core of issues like climate change denial and the anti-vaccination movement. Scientific literacy is a huge and complex problem, but I think one cause of this mistrust is how few people know a scientist personally (in fact, one study found that only 4% of Americans could name a living scientist). People tend to trust people they know, so with that in mind I’ve decided to get more involved in science outreach.

I have now visited two local junior high school classrooms through The World in Your Classroom, a program that brings foreigners living in Taiwan into classrooms to meet with Taiwanese students and tell them about their home countries. I’ll describe one of those experiences now.

For the first thirty minutes or so I showed the students some slides talking about where I grew up and how I ended up in Taiwan. In advance, their teacher had sent me a list of questions from the students. They certainly knew a lot more about America than I knew about any foreign country when I was their age, and they weren’t afraid to ask the hard questions. Examples were “Do you support the US maintaining good relations with China?”, “Who did you vote for in the last presidential election?” and “What is your opinion on racism and same-sex marriage?”. Many of their questions asked whether America was friendly to immigrants, to which I said yes. (I imagine news coverage of current events might have inspired those questions). I did not talk extensively about my research, but I did talk about what it’s like to be a scientist and why I like my job. I especially wanted to address the misconception that scientists are all supergeniuses, so I made sure to point out that I was a very poor student when I was their age and I struggled quite a lot in school. They responded really well to this message.

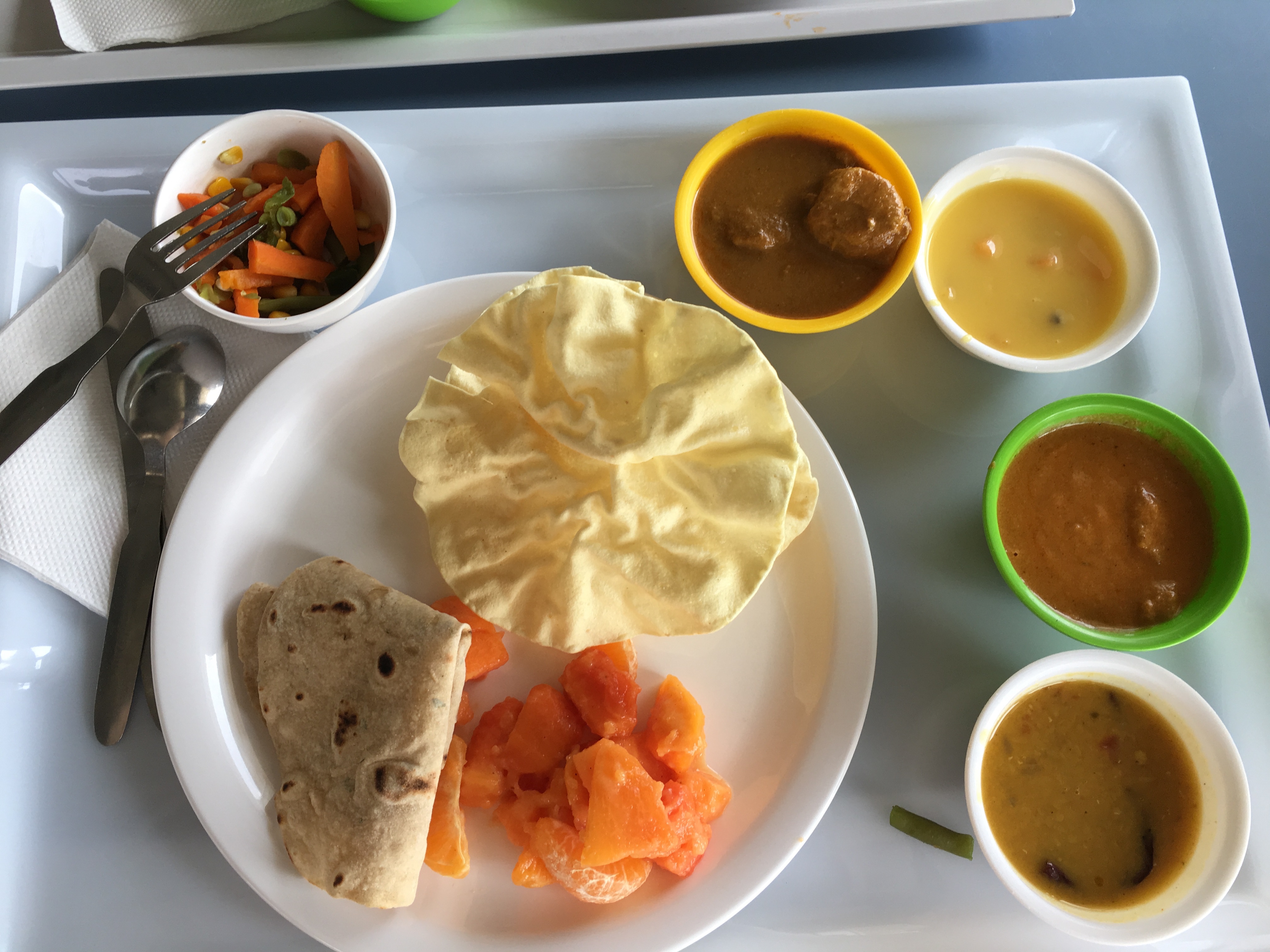

For my trouble I was given a few small gifts, including a box of the best pineapple cakes I’ve had so far (I really need to figure out where those came from). I’m looking forward to meeting more Taiwanese students in the future.